It is at this time of year that Jews spend time in self reflection and assessment. The Jewish New Year or Rosh Hashanah, which begins tomorrow, starts a ten day period which culminates with Yom Kippur, the day of atonement. We can generally separate reflection into two categories: reflection on behaviour and reflection on attitude. The former focuses on how we act as human beings, how we treat others, our level of productivity and our personal moral and spiritual conduct. Reflection on attitude, conversely, has to do with the beliefs, opinions and views we hold. Often we spend time reflecting on how we acted over the past year but devote little time to reviewing our attitudes and strongly held views.

But in the confessions of the Yom Kippur liturgy forgiveness is also sought for sins which we have committed by improper thoughts and by a confused heart. This, in my view, is referring to sins associated with improper beliefs and opinions. We often take it for granted that the opinions and attitudes we hold are necessarily the correct ones. Asking people to question their deeply held beliefs is especially challenging in a community that demands an unwavering and unquestioning doctrinal belief.

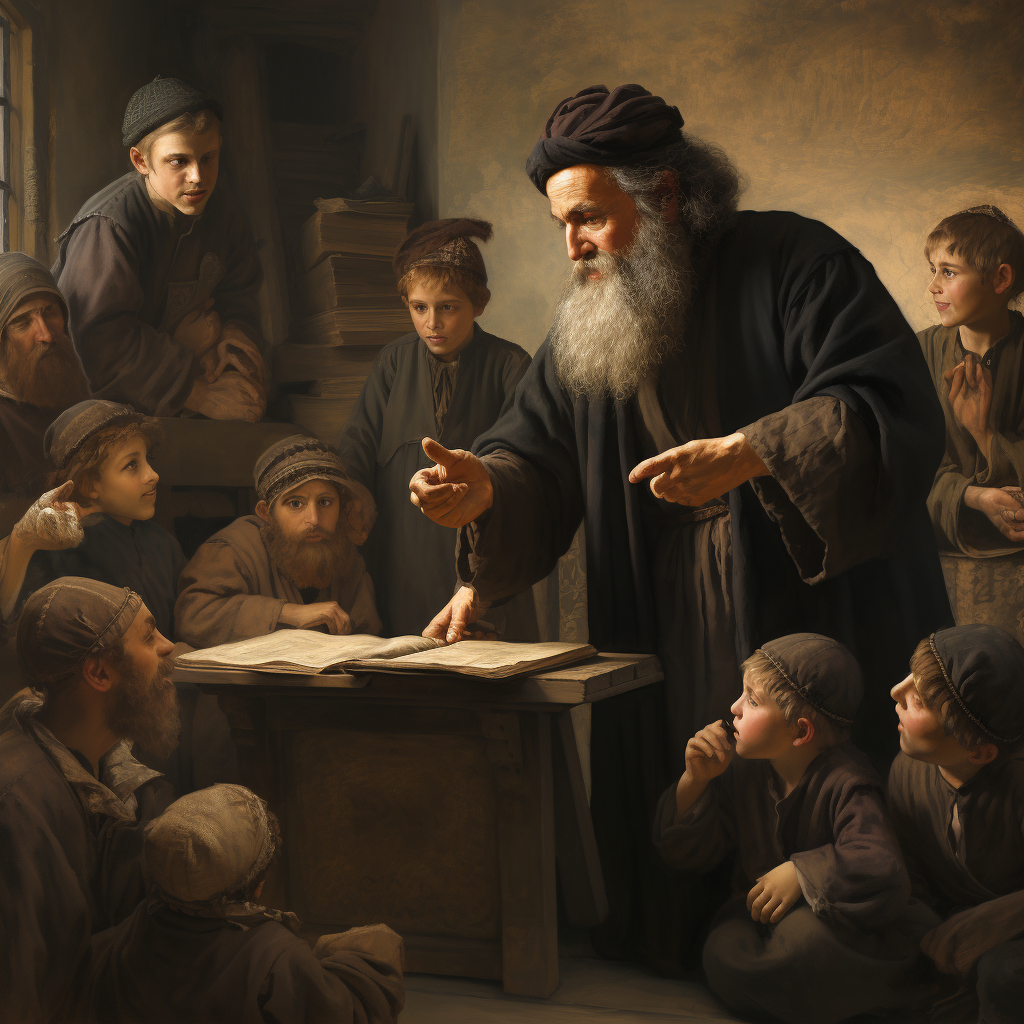

There was a time, however, when Jews were open to examining their beliefs. In the 900’s the great Jewish sage Saadia Gaon wrote a book titled ‘The Book of Beliefs and Opinions ‘ where he examined Jewish doctrine. In the 1200’s Maimonides wrote his seminal work ‘The Guide to the Perplexed ‘ where he radically redefined certain Jewish beliefs and theological ideas. Writing in the 1000’s the Jewish ethicist and philosopher Bahya ibn Paquda was explicit about the need to thoroughly and critically reflect upon the fundamentals of faith.

This type of reflection led to real progress within our dogma and religious beliefs. When Maimonides, for example, concluded that an anthropomorphic beliefs about God were mistaken — despite the fact that other great rabbis disagreed — he made his opinion known and in time normative beliefs changed in line with the new Maimonidean perspective.

As Judaism moved into the dark ages, however, the tradition of reflecting on matters of belief and doctrine started to become taboo. In many circles, reading books that analyzing matters of belief and faith, even those written by the likes of Maimonides and Saadia Gaon, was discouraged. This continues to this day. In an annotated edition of Bahya ibn Paquda’s ‘Duties of the Heart ‘ published about fifty years ago in Jerusalem, the modern day annotator adds many pages of warning to the reader not to read the section that deals with matters of belief. Needless to say no commentary or annotation is offered for that section of the book.

In some religious circles there is open antagonism towards reflecting critically on matters of belief and opinion. As a Yeshiva student nearly two decades ago one of my most revered teachers threatened to never speak to me again if I read even a rabbinic book that examined Jewish beliefs and opinions.

But the endemic lack of self reflection when it comes to matters of belief and doctrine is deeply problematic. When a mistaken belief or opinion develops there is no mechanism remove or improve it.

Although I do not have a particular one in mind, there are without doubt some mainstream religious doctrines that are worthy of deep reflection and honest reassessment. When it comes to improvement of character Judaism suggests that we can make progress by setting aside time — chiefly during the High Holidays — to reflect on our deeds and then do away with any harmful or negative practices and behaviors that may have crept in over time. For us as a people to make progress we need to do likewise. To be successful, however, no element, no matter how uncomfortable they may make us feel, can be off limits to that sort of critical reflection.